Malnourished S.C. Toddler in DSS Custody Returned to Family only when "DSS Didn't Want Blood on its Hands."

Now thriving again in the care of family, it took their toddler being diagnosed with failure to thrive and being worked up for a feeding tube before he was eventually placed in kinship care.

Precipitating Event in the Home

Kershaw County mom, FB, described volatile struggles with teenagers adamantly insisting on more independence. Her older children from a prior relationship were being raised with their much younger half-siblings until the spring of 2022 when the eldest wanted to pursue being emancipated.

The mother was distraught, fighting this tooth and nail until it escalated into what FB described as an attempt to physically bar her eldest from leaving home. Though no physical injuries required medical attention, local law enforcement - which has unilateral authority to place children in emergency protective custody (EPC) in South Carolina - facilitated all four (4) children being taken by the Department of Social Services (DSS) for their “safety and protection.”

Baby Needed Special Care

The youngest of FB’s children is a boy born in early 2021 with craniosynostosis, a condition caused by the premature fusion of the skull for which he required neurosurgical intervention early in life. Parents prayed that their child would eventually be able to walk, and they obtained leg braces to help stabilize and support his lower extremities.

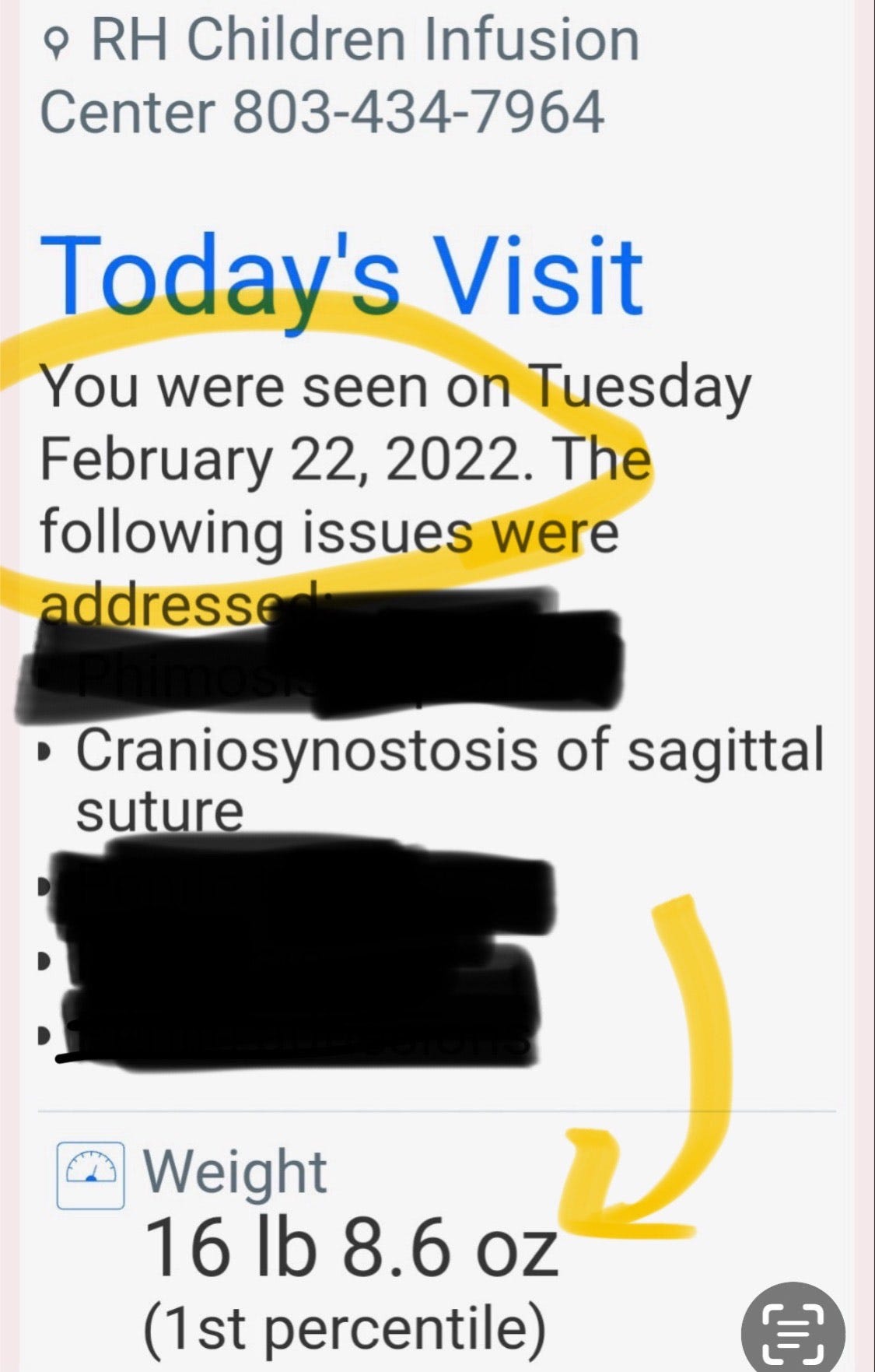

According to records from Prisma Health, their son weighed 16 lbs, 8.6 ounces the last time that his mom took him to the pediatrician. That was on February 22, 2022, approximately 6 weeks prior to DSS having custody of the one-year-old, the teen boys, aged 14 and 17 years, and her 8-year-old daughter who were placed in a single foster home.

Though the two teens were described as independent, strong-willed, with street smarts and survival skills, the two littles needed vastly different care. FB described initially having regular supervised visits with DSS case managers and each of her children. For their fragile and special needs baby, mom said she routinely asked such questions like the following:

“Is he eating enough?

“Why can’t he go live with grandparents?”

Are medical appointments being attended?

Is he up to date on everything with the neurosurgeon’s office?

Are you sure he is growing?

Why is he so thin?

Is he wearing his leg braces?”

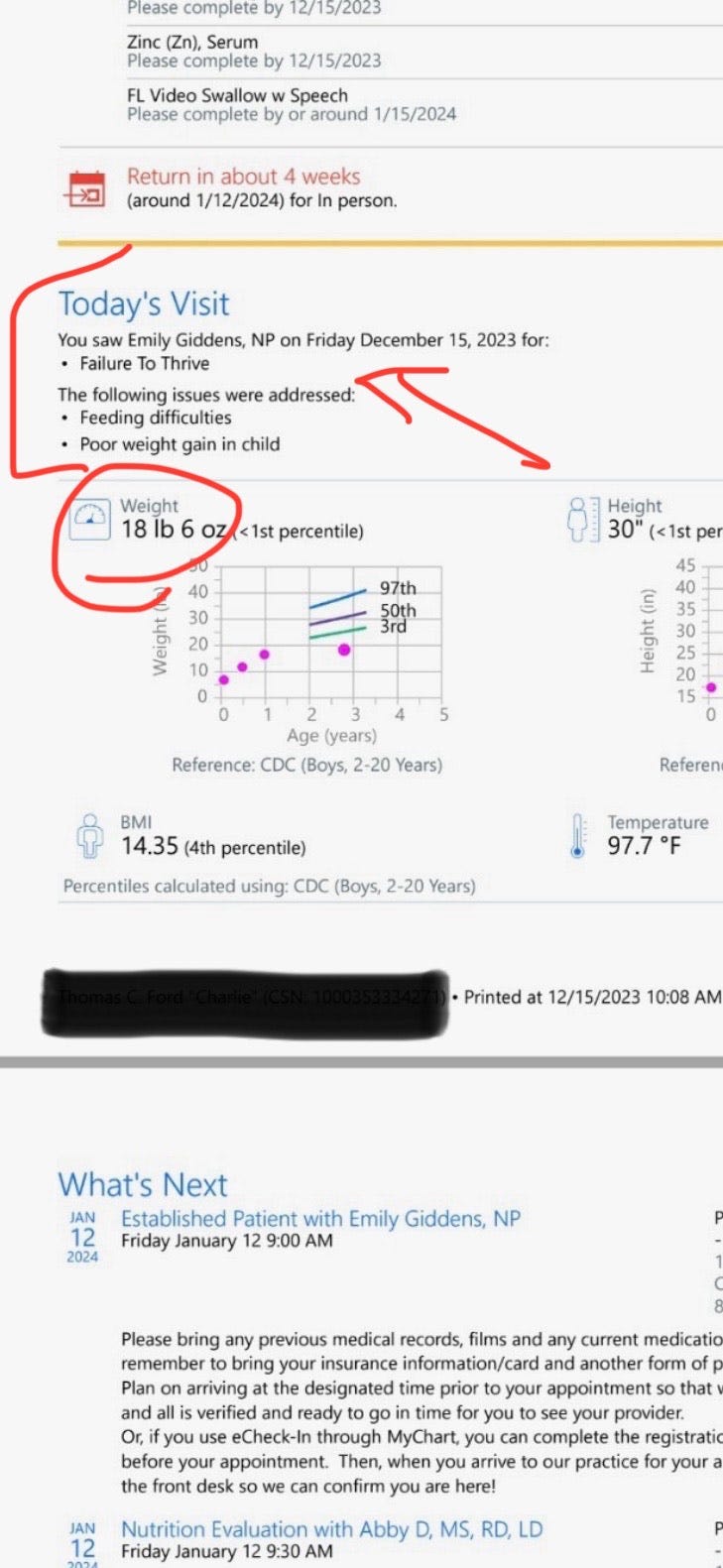

Unfortunately, the mom’s concerns were not given credence for 20 months. On December 15, 2023, Prisma Health records show that her son’s weight was only 18 lbs, 6 ounces indicating he had gained less than 2 pounds in 20 months. At that time, their youngest was diagnosed with failure to thrive, feeding difficulties, and poor weight gain; FB was told her son would likely require a feeding or gastrostomy tube.

Though South Carolina is a “kin first state,” which should drastically increase the numbers of children being able to reside with relatives while their home environment is not able to meet their needs, many parents report that DSS workers are often not amenable to this option — and such was the case for FB.

Mom reports that it was only when their son’s malnourished and neglected condition was a deemed to be a medical emergency that DSS considered the kinship option. FB wholeheartedly believes that an intervention only happened when medical professionals sounded the alarm on her son’s care making DSS concerned that he may not survive much longer without a substantial change in his circumstances. She contends that DSS did not want her child’s blood on their hands.

Admitted Shortcomings by DSS

As part of Michelle H. vs. McMaster, a landmark class action lawsuit representing thousands of children across the state who were neglected in DSS care, two nationally known child welfare experts serve as independent co-monitors of S.C.’s progress. Periodically, the experts issue public reports on the state’s progress toward ensuring the benchmarks for children’s basic needs that are outlined in the settlement.

According to a 2023 progress report published by one of the co-monitors, DSS has plenty of excuses while it admits to continuing to be ill-equipped, inadequately trained, and essentially a disaster for children. Lacking homes and caregivers for children, unable to provide routine meals or medication, education opportunities, hygiene items, medical care, oversight, clothing, socialization, etc, appears the norm for the past decade.

Some excerpts from the recent report:

'“Regardless of whether they are sleeping overnight in a DSS office, or spending a few hours in a stranger’s home, a significant number of children in DSS’s custody at any time are effectively homeless.”

“We have medically fragile children with special needs, and we’re held responsible for assessing safety, but we’re not trained…We can’t do medication management. We don’t have the ability to recognize and prevent escalation. We work well together but we’re human – we don’t have the ability to continue to serve the children.

“While at emergency placements, children are sometimes barred from bathing, eating meals, accessing their phones, and taking their medication.”

Thankfully, in the case of FB and family, their son is now thriving in the care of family, gaining significant weight and showing excellent potential, even “chubby.” Situations like this certainly makes one wonder, how many children are suffering unnecessarily in DSS care when there is family who is able, willing, and fit to care for them?

Former CASA (Court Appointed Special Advocate) here. This is unnecessary.

Utterly unconscionable.